Personal Variants on Parisian Cubism

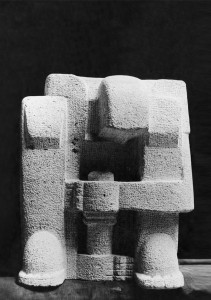

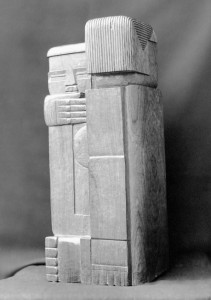

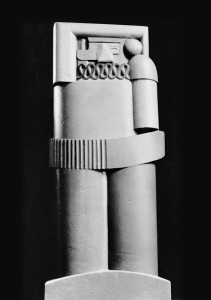

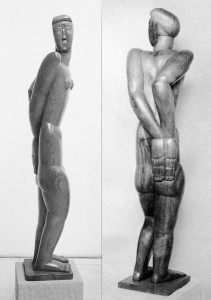

After several years of research and with Paul van Ostaijen’s encouragement, Oscar developed his own personal expression within Cubism, where the human figure is not fragmented, as was the trend in Paris. Referring to De pottendraaier, van Ostaijen wrote that the cube had become the fundamental form of everything. Jespers showed increasingly the body or the head intact and the cube, sphere and oval forms all assisted in providing his sculptures with a solid consistency. This technique applies to all his artistically important work created in the Twenties. For example, De jongleur (The Juggler) was constructed from two cylinders. The juggler and circus characters in general were at the time an international inspiration in the fine art and poetry world. When Jespers used two tiny pots of paint to colour one of the juggler’s legs green and the other one blue, his only explanation was that ‘it needed it’. During the 1920s, he loved to self-impose one or other severe restriction. This was the case, among other reasons, when in 1925 he created Het Toilet from an old stone threshold belonging to a church in Ostend: a monumental female figure with the reverse side revealing a motif of a lyrical, almost musical repetition. Year after year the artist favoured working with Belgian Bluestone. However, cutting into it released a pungent unpleasant odour that consequently persisted to permeate his whole workshop. In the Twenties it seemed as if this formally rigorous point of departure fuelled Jespers’ creativity.

Art Deco in the Twenties

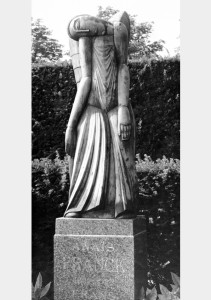

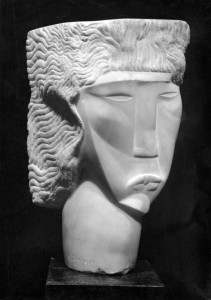

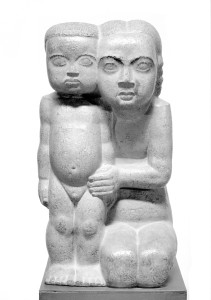

Several of Jespers’ sculptures dating from the Twenties show an affinity with the Art Deco movement. He even succeeded to combine his admiration for Egyptian sculptural art with his own artwork. For example, with the Kleine ruiner (Small Rider) Jespers conceived the eyes of the mother and the child as if they were facing forward, while they are actually both in profile: an artistic choice often found in hieroglyphics. Similarly, the mother’s hairstyle is reminiscent of wigs worn by Egyptian courtiers. The decorative artwork over the entire surface and the highly stylised forms that emerge from this piece are characteristic of Art Deco. Similarly, Engel (Angel), a monument that Jespers sculpted in 1927 to stand over the grave belonging to Anaïs Franck, located in the Schoonselhof cemetery in Antwerp, also displays Art Deco features: the upper part of the torso extended and lower torso shortened, upper arms shortened and the forearms lengthened. Also, the grief revieled by the inclination of the head, tilting to rest on the shoulder, shows an extremely stylised expression in keeping with the best tradition of Art Deco.

Affinity with Brancusi

Stubborn Cubism

Expressionism

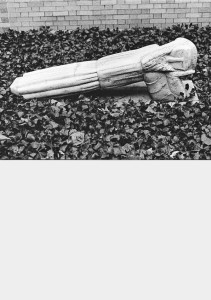

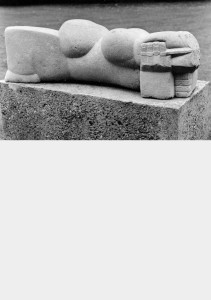

De bekoring van Sint Antonius

(The Temptation of Saint Anthony)

1933, Bluestone

146 cm L.

MoMA, New York

In 1927 the sculptor and his wife, Mia Jespers-Carpentier, moved to Brussels. Henry van de Velde had invited him to teach at the Hoger Instituut voor Decoratieve Kunsten in Brussels, also known as La Cambre. On December 14th of that same year, Oscar and Mia unexpectedly lost their only child, Hella. This tragic event prompted the artist to seek, as he himself expressed, “more humanity” in his work. His friends, the Expressionist painter Gustave De Smet (1877-1943) and Constant Permeke (1886-1952) encouraged this shift in his artistic exploration. The subject matters explored by the Flemish expressionists were: love of life, birth, growth and to a lesser extent their contrast: death. This positive and substantive orientation in Jespers’ work method is also reflected in the subject matter of Jespers’ Expressionist pieces, and named appropriately; such as Geboorte (Birth) and Moederschap (Maternity). Similarly, his piece called De bekoring van Sint Antonius (The Temptation of Saint Anthony), which is on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, exudes existential values.

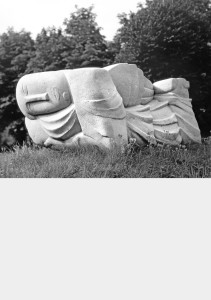

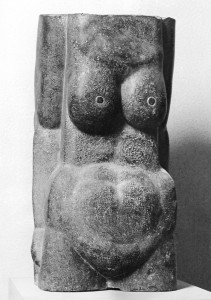

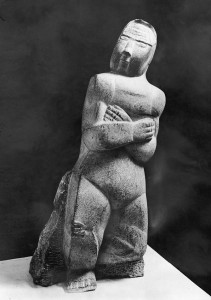

Geboorte (Birth) was inspired by the arrival of Paul, Oscar’s only son and cut in 1932 from Belgian Bluestone, being the stone that Jespers chose for most of his Expressionist sculptures. The powerful expression is created by the contrast between the rounded form of the belly and breasts placed in juxtaposition to angular knees, arms and hands. Also, the woman in labour is compelled to use her immense hand to repel the physical suggestion to cry out from pain. Furthermore, a large part of the sculpture is in contact with the ground. All these features contribute to the Expressionist ideology, characteristics also evident in Engel (Angel), Funerary Monument for the Poet Paul van Ostaijen. This monument, located in Schoonselhof cemetery in Antwerp, depicts an angel guarding and mourning a life cut short too young.

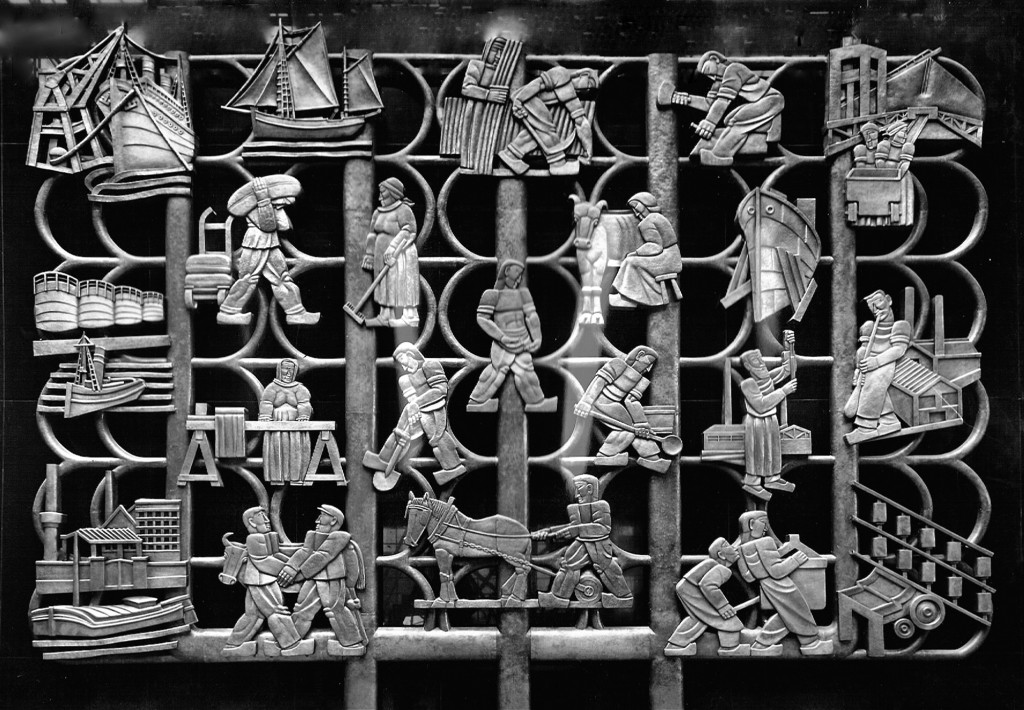

A Monumental Relief

België aan het werk

(Belgium at Work)

1936-’37, gilded brass

600 x 600 cm

side facade of the

Stadsschouwburg, Antwerp

België aan het werk (Belgium at Work), commissioned by the World Exposition in 1937, held that year in Paris. This early Expressionism shows vigorous characters making a meaningful contribution to the prosperity of Belgium: a rather telling and narrative piece.

Terracotta Female Figures

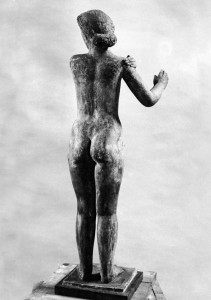

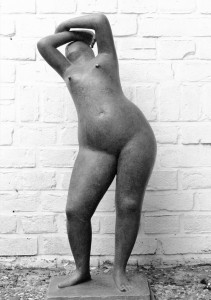

During the Second World War sculptors found it difficult to obtain high quality stone, clay was an alternative. Using a wire-thread, Oscar Jespers would slice a slab out of a block of clay then model it into a round form: arms and legs then had the required hollow shape needed for firing. One of the purest forms he built using this technique was the 78 cm high Purity. At a later date he cast this same piece out of bronze, thus the transition towards the next period: bronze female figures.

Female Figures in Bronze

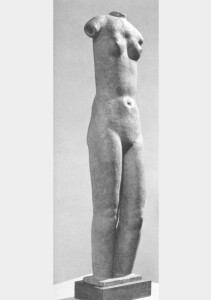

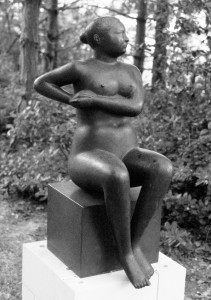

Between 1946 and 1947, Jespers cast three female figures out of Gypsum and named all three In de zon (In the Sun). Compared to the Expressionist statues, these figures appear to be closer to reality, of everyday life, but this impression is deceptive. They actually depict women as a myth, specifically the myth of perfection and fecundity. The same deception applies to Leunende vrouw (Woman Leaning), made in this same period.

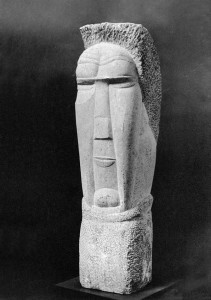

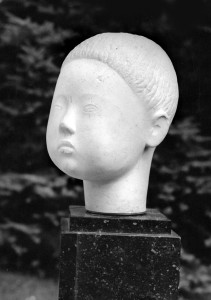

A Few Heads

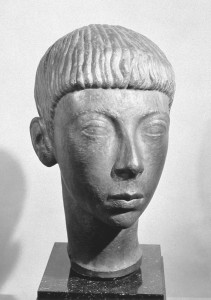

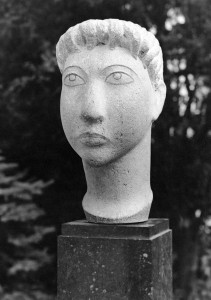

Sculpting childlike heads was another subject matter loved by Jespers. In 1927-28 he created Babykop (Baby Head) in white marble. The extreme roundness symbolises the singularity of this new life. In 1942 he managed to immortalise in Bluestone the head of his thirteen year old son, Paul: a young life containing the dormant seeds of all his future talents. His hair is styled to look like a helmet, similar to those found on ancient Greek sculptures. The portrait of his grandson Stéphane, made from white marble in 1960, lies between these two works. The adults and the elderly whose portrait Jespers created experienced a rejuvenation in his hands.

Little Leda and the Swan

Kleine Leda met de zwaan

(Little Leda and the Swan)

1963-65, white marble

34 x 24 x 23 cm

Private collection, Netherlands

Jespers completed Kleine Leda met de zwaan (Little Leda and the Swan) in 1963, yet he signed the sculpture only in 1965. The story of the Metamorphoses of Ovid, tells how the great god Zeus transformed into a swan so that his jealous wife would not realise that he was courting the beautiful Leda. With its triangle-shaped base and undulating volumes, this white marble sculpture expresses plenitude and satiety. Combining strength and precious beauty, Kleine Leda met de zwaan provides a synopsis of Jespers’ sculptural oeuvre.

Nederlands

Nederlands Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch